If the sudden assassination of

Indira Gandhi in 1984 proved to be a great shock for both India and the rest of

the world, the assassination of her son 7 years later proved to be equally

shocking. Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination came amidst rocky times for the nation

of India, during an era when the country was just recovering from the aftermath

of Indira’s assassination and was itself mired in much political instability,

both internally and externally.

Rajiv Ratna Gandhi (Hindi: राजीव रत्न गांधी) (1944 – 1991) was the sixth

Prime Minister of India, serving from 1984 to 1989. Eldest son of the third

Prime Minister of India, Indira Gandhi (Hindi:

इन्दिरा गाँधी) (1917 – 1984), and grandson of India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal

Nehru (Hindi: जवाहरलाल नेहरु)

(1889 – 1964), Rajiv was never interested in politics until the sudden death of

his younger brother, Sanjay Gandhi (Hindi: संजय गांधी)

(1946 – 1980), who died in a plane crash in 1980. Sanjay was Indira’s preferred

choice as her successor, but his death meant that Rajiv had to be persuaded to

take over his brother’s role in India’s political arena. He thus left his dream

career of being a pilot for Indian Airlines at the behest of his mother. He won

his brother’s parliamentary constituency the following year and was groomed by

his mother to take over the leadership of the Indian National Congress.

Right after his mother’s assassination

on 31 October 1984, Rajiv was urged to succeed her as Prime Minister. He was

sworn in within hours after her death, consequently being forced to lead a country

that was in chaos as public anger against Sikhs mounted in the aftermath of

Indira’s death. Soon after succeeding premiership, Rajiv called for the

dissolution of parliament, paving the way for a general election at the end of

that year. Rajiv’s Indian National Congress won a landslide victory with the

largest majority in Indian history, giving him strong control over the

government.

Rajiv and his mother, Indira, when she was still Prime Minister

Although his government was able to quell the

anti-Sikh riots in subsequent days, he was still resented by many in the Sikh

community, particularly those who were supportive of the Khalistan movement

(i.e. the establishment of a separate Sikh country called Khalistan (Punjabi:

ਖਾਲਿਸਤਾਨ)) and those who

were offended by Indira’s decision to send a military operation into the Golden

Temple (Punjabi: ਹਰਿਮੰਦਰ ਸਾਹਿਬ, Harmandir

Sahib) in Amritsar (Punjabi: ਅੰਮ੍ਰਿਤਸਰ). Additionally, in the

aftermath of the anti-Sikh riots, he was quoted to have said:

“Some riots took place in the country following the

murder of Indira-ji. We know the people were very angry and for a few days it

seemed that India had been shaken. But, when a mighty tree falls, it is only

natural that the earth around it does shake a little.”

This statement

reportedly did not go down well with the Sikh community in general, who felt

the authorities were siding the anti-Sikh rioters and were deliberately taking

slow and lenient action against the rioters so as to allow a degree of

victimization against the Sikhs. It was thus no wonder that Sikh militants were

among the prime suspects behind Rajiv’s assassination in 1991. After all, there

had been an attempt on his life by a Sikh assassin in 1986.

Nonetheless, the perpetrators came not from the north (i.e. the state of

Punjab (Punjabi: ਪੰਜਾਬ)), but rather from

the south (i.e. the country of Sri Lanka (Sinhala:

රී ලංකාව)).

Anti-Sikh riots in 1984 after the assassination of Indira Gandhi

Before going into the details leading up to

Rajiv’s death, it is worth having an overview of Sri Lanka’s demographic

composition and the background of the country’s civil war. The Sinhalese form

the island-nation’s largest ethnic group, comprising approximately three

quarters of the population. Tamils form the second largest ethnic group,

comprising about 10% of the population and are mainly concentrated in the

northern and eastern parts of the island. Since Sri Lanka’s independence from

the British in 1948, numerous legislations and policies were passed by the

Sinhalese-dominated government that were seen as discriminatory towards the

island’s Tamil minority. As a result, anger within the Sri Lankan Tamil

community brewed over the decades, finally triggering a civil war in 1983.

Location of India and Sri Lanka

The civil war, waged by several Tamil

militant groups against the Sri Lankan government, sought to establish an

independent state of Tamil Eelam (Tamil: தமிழீழம்), covering the Tamil-majority

areas

in Sri Lanka. Among these militant groups, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam

(LTTE) (Tamil: தமிழீழ விடுதலைப் புலிகள், Tamilila Vitutalaip

Pulikal), or Tamil Tigers in short, stood out the most, with its leader Velupillai

Prabhakaran (Tamil: வேலுப்பிள்ளை பிரபாகரன்) (1954 – 2009) being a firm believer and

a fierce fighter for the Tamil Eelam cause.

In the

years prior to the start of the civil war, LTTE and other Tamil militant groups

in Sri Lanka formed strong ties with various political parties in the Indian

state of Tamil Nadu (Tamil: தமிழ்நாடு), where Tamils form the majority. These

political parties threw their full support behind the Tamil Eelam cause and

even offered the state as a sanctuary for the militants, in addition to

supplying them with arms, ammunition and training. Not wanting to antagonize

the overwhelming support in Tamil Nadu, the Indian government under Indira and

subsequently Rajiv initially chose to sympathize with the Tamil Eelam movement.

Velupillai Prabhakaran (1954 - 2009) (Tamil: வேலுப்பிள்ளை பிரபாகரன்), leader of the Tamil Tigers

Velupillai Prabhakaran with soldiers of the Tamil Tigers

When Rajiv succeeded the premiership, he

wanted to establish friendly relations with India’s neighbours, but at the same

time wished to avoid antagonizing Tamil sentiments in Tamil Nadu. As the civil

war raged, the Sri Lankan government rearmed itself and by June 1987, it succeeded

in laying siege on the city of Jaffna (Tamil: யாழ்ப்பாணம், Yālppānnam), LTTE’s

centre of operations. The siege resulted in large civilian casualties, which

quickly escalated into what was seen as a humanitarian crisis especially in the

eyes of the Tamils in Tamil Nadu. Fearing a Tamil backlash, the Indian

government called on the Sri Lankan government to stop the attacks and

negotiate a peaceful settlement, but to no avail.

The Indian

government had to be seen to be doing something in favour of Tamil sentiments

back home. A convoy of unarmed Indian ships carrying humanitarian assistance

was sent to northern Sri Lanka but this was intercepted by the Sri Lankan navy

and was asked to turn back. After the failure of this mission, the Indian Air

Force flew over Jaffna to airdrop supplies to civilians, in a show of force by

the Indian authorities. Strict warnings were given by the Indian Foreign

Minister to the Sri Lankan High Commissioner in New Delhi that if the operation

was in any way hindered, India would not hesitate to launch a full military

retaliation against the island-nation.

Residents of war-torn Jaffna in Sri Lanka

Such display of

military force by the Indian government alerted the Sri Lankan President,

Junius Richard Jayewardene (Sinhala:

ජුනියස් රිචඩ් ජයවර්ධන) (1906 – 1996)

to the possibility of active Indian military intervention in Sri Lanka’s

internal affairs. He thus offered to hold talks with the Indian government, at

the same time lifted the siege of Jaffna. The talks resulted in the signing of

the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord between Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and President Jayewardene

on 29 July 1987. Terms in the accord included the withdrawal of Sri Lankan

troops, the disarming of the Tamil insurgents and concessions to several Sri

Lankan Tamil demands, such as devolution of centralized power to the

Tamil-majority provinces, merger of the Tamil-dominated northern and eastern

provinces subject to later referendum, and official status for the Tamil

language. Notably, however, the LTTE and other Tamil militant groups were not

made to be part of these talks.

Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and Sri Lankan President J.R. Jayewardene signing the Indo-Sri Lankan Accord on 29 July 1987

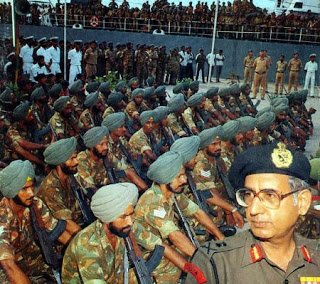

As per the

conditions laid out in the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord, the Indian Peace Keeping

Force (IPKF) (Hindi: भारतीय शान्ति सेना, Bhāratīya Sānti Sēnā) was formed under the

Indian military and was sent to Sri Lanka to end the civil war. Initially, the

IPKF was not expected to engage in any major combat, as the LTTE and other

Tamil militant groups had agreed to disarm peacefully, albeit reluctantly.

Nevertheless, after the formation of an Interim Administrative Council under

the IPKF, differences came in between the IPKF and the LTTE, in which the

latter did not only attempt to dominate the council, but also refused to

disarm. These differences culminated in a combative attack against the IPKF,

after which it was decided that they would disarm the LTTE, by force if

necessary. A series of combats between the two ensued.

Sri Lankan soldiers engaged in the civil war against the Tamil Tigers in northeastern Sri Lanka

The presence of

the IPKF in Sri Lanka soon became unpopular, as the Indian force was also

accused of its fair share of human rights violation on Sri Lankan ground. When

President Jayewardene retired from active politics at the start of the new year

in 1989 and Ranasinghe Premadasa (Sinhala:

රණසිංහ ප්රේමදාස) (1924 – 1993)

succeeded him, the latter called for the withdrawal of the IPKF, but was met

with refusals from Rajiv’s government. Nonetheless, the IPKF mission itself,

coupled with other issues pertaining to corruption scandals and increasing Sikh

unrest in Punjab, resulted in the ousting of Rajiv’s Indian National Congress

from government in the 1989 general elections held in November. Vishwanath

Pratap Singh (Hindi: विश्वनाथ प्रताप

सिंह) (1931 – 2008), who succeeded Rajiv as Prime

Minister, ordered the gradual withdrawal of the IPKF, and its last troops were

completely withdrawn from Sri Lanka by March 1990.

Withdrawal of the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) from Sri Lanka in 1990

Barely two years after the 1989 general

elections, another general election was called for in May 1991, which saw the

possibility of Rajiv returning to power. Fearing the possibility that Rajiv

might reinitiate the IPKF’s efforts to disarm and destroy the LTTE should he

return to power, the latter’s leader, Vellupillai Prabhakaran, decided that a

major clandestine mission should be undertaken to eliminate this possibility.

What exactly was this major clandestine

mission that Prabhakaran had devised? And was it successful? Proceed to the

next part of this article if you’d like to find out.

No comments:

Post a Comment