Father Alessandro Valignano

We would perhaps be doing Father Alessandro Valignano great injustice if we do not cover about him in our discussions and overview of Catholic Christianity in Japan. Father Valignano, whose farsightedness, leadership and contributions made immensely outstanding progresses in the expansion of Christianity in Japan, is frequently dubbed the second greatest missionary to the Land of the Rising Sun after Francis Xavier. Since his contributions encompass missionary work in both Kyushu Island and central Japan, I will dedicate this part of the article to this great apostle to Japan.

Alessandro Valignano (1539 - 1606), Neapolitan (presently Italian) missionary to Japan and China

Father Alessandro Valignano (1539 – 1606), who was born in Chieti, Italy, is renowned not only for his remarkable contributions to Catholic Christianity in Japan, but also for his significant contributions to the spread of the gospel in imperial China during the later era of the Ming Dynasty. The great missionary always had special interest for the spread of the gospel and the progression of Christianity in the East. Thus, the Jesuit authorities in Rome made the best choice in appointing him as Visitator General for all the Jesuit missions from Africa to Japan in August 1573. As Visitator General, his responsibilities include visiting, inspecting and administrating Jesuit missions that have been established throughout all the regions ranging from Africa to the Far East.

Being Visitator General, Father Valignano could not stay in any single location, including Japan, for a long period of time, unlike most other missionaries under him. He, however, held special administrative authority in the Jesuit hierarchy to carry out reformations and changes to local missions under his purview, as and when he saw fit. Therefore, although he could not remain in Japan for a very long period of time, he managed to channel his contributions to the expansion of Christianity there by means of several visits, each lasting for only a few years. To make matters simpler, we will now go through his missionary activities and efforts in separate sub-sections covering each of his visits to Japan.

First Visitation to Japan (1579 – 1582)

Father Valignano’s first visitation to Japan began when he set out from Macao in 1579 and arrived in the town of Kuchinotsu (口之津) on the island of Kyushu in the same year. His maiden trip to the Land of the Rising Sun did not bring him the joy that he had expected after hearing many positive reports and remarkable successes about the spread of the gospel there. Indeed, upon realizing the errors that occurred under Father Francisco Cabral, then Mission Superior, or head of all the Jesuit missionaries in Japan, Father Valignano found himself to be at loggerheads with Father Cabral as the former tried to reform certain aspects of the mission there for the better. What was it, then, that had upset Father Valignano?

Father Alessandro Valignano

It cannot be denied that under Father Cabral’s leadership, Christianity had made substantial progress, especially with the increasing numbers of Japanese daimyos, nobilities and commoners receiving baptism and professing the Christian faith. Nonetheless, one weakness, and in fact a grave one, that occurred under Father Cabral’s leadership was the fact that missionaries under him, and including himself, frequently held to their opinion that Western culture was more superior than Japanese culture. As a result, he and the missionaries under him made little effort to acquire any in depth understanding and appreciation of the Japanese culture. They were blatantly disagreeable with adapting Japanese culture into Christianity wherever possible, and always promoted Western values over Japanese customs in propagating the gospel. No doubt, such an attitude towards Japanese culture would be suicidal for Christianity in a long-run, especially in a nation where customs and traditions are perceived with much importance, even up to this day.

Realizing this grave error in the Jesuit mission in Japan, Father Valignano initiated several reformations in his capacity as Visitator General. Father Cabral, though being very committed to the spread of the gospel in Japan, could not see eye to eye with Father Valignano on this matter, thus he tendered his resignation as Mission Superior in 1582.

Ladies in kimono - an integral part of traditional Japanese culture

Among the reformations that Father Valignano initiated was to encourage all Jesuit missionaries coming to Japan to learn the Japanese language, customs, traits and perspectives in order to have a sound appreciation of the nation’s culture. Father Valignano was also a strong proponent of accommodating Japanese culture and traditions into Christianity wherever possible. He drafted out guidelines for missionaries to follow in adapting to Japanese culture, which thus became useful in giving a more favourable impression of Christianity to the Japanese people.

If you recall what I wrote earlier on, you would remember that the port of Yokoseura, which was within the Omura Domain, became a prominent Jesuit missionary centre after the mission in Hirado was destroyed. However, another riot that broke out in Yokoseura in 1570 resulted in the annihilation of the missionary centre there as well. Omura Sumitada, the daimyo of the Omura Domain, who was himself already baptized as a Christian at that time, offered them the port-village of Nagasaki as their next location to reestablish the destroyed missionary centre. Besides granting the Jesuits the permission to establish a mission in Nagasaki, Sumitada also granted huge sums for developing the insignificant port-village, subsequently transforming it into a bustling port-city and centre for Portuguese trade merely within the span of several years. Consequently, the population of Nagasaki grew extremely rapidly, from a mere 1500 in 1570 to more than 30,000 after several years, almost all of whom were Christians. Dubbed the “Japanese Christian city” of the era, Nagasaki also became a haven for Japanese Christians from other parts of Japan who were persecuted and had fled from their original homes.

Location of Nagasaki (長崎) in Japan

When Ryuzoji Takanobu (龍造寺隆信) (1530 – 1584), a neighbouring non-Christian daimyo from northern Kyushu, started threatening Omura Sumitada and attempted to wage war against him, Sumitada decided to cede the port-city of Nagasaki to Father Valignano in order to prevent the Japanese Christian city from falling into the hands of a non-Christian daimyo, should Sumitada lose the war. Subsequently, an agreement was reached, whereby Sumitada would have a portion of the mercantile profits derived from Nagasaki, while the Jesuits would have full administrative powers over the port-city. With that, Nagasaki became somewhat a “Jesuit colony” which remained under Sumitada’s protection.

Nagasaki’s cession to Father Valignano and the Jesuits was vital for the funding of the Jesuit mission in Japan. With seminaries being built, churches mushrooming throughout Kyushu and central Japan, and staff increasing in number, more funding was required to fuel all these rising financial demands. Funding from Europe came irregularly, and funding from Portuguese traders sometimes proved to be unreliable, as they were dependent on many trade risks. Most Japanese Christians were not very well off to provide much funding for the Jesuit missions, whereas there were limits as to how much Japanese Christian daimyos could fund the Jesuit missions, since most of them were engaged in continuous wars. Hence, the Jesuit missionaries in Nagasaki had no choice but to be involved in trading as well, so as to generate sufficient profits to fund the Jesuit missions. This undoubtedly raised many eyebrows among the Jesuit superiors in Goa and Rome since Catholic priests are normally not allowed to engage in secular activities such as trading, but Father Valignano defended his decision, asserting that it was an unavoidable necessity if the Jesuit missions in Japan were to receive continuous adequate funding.

Japanese depiction of Portuguese traders in Japan

Besides all these, Father Valignano was also instrumental in the establishment of the first ever seminary on Japanese soil. Seeing the need to raise a Japanese clergy to meet the spiritual needs of the Japanese Christians and solidify the position of Christianity in Japan, Father Valignano proposed that a seminary should be established to educate talented Japanese Christian children on Japanese and European culture, philosophy, humanities and theology. This proposal was realized with the support of another Christian daimyo, Arima Harunobu (有馬晴信) (1567 – 1612), who provided the grounds and building to Father Valignano for the purpose in 1580.

The latter half of Father Valignano’s first visitation was spent in central Japan, when he arrived in Sakai in March 1581 and was warmly welcomed by the Christians there. From Sakai, he then went on to Kyoto, where he met Father Frois. With Father Frois’ arrangement, Father Valignano was able to have an audience with Oda Nobunaga and obtain permission from the great daimyo to establish a seminary in Azuchi, the new city which Nobunaga constructed for himself. Thus, the second seminary in Japan was established with support from Nobunaga himself.

A comic-style depiction of Father Alessandro Valignano (left) and Father Louis Frois (right) having an audience with Oda Nobunaga

Indeed, Nobunaga had been very well-disposed towards Christianity, the Jesuit missionaries and the Japanese Christian communities as a whole, despite being a non-Christian himself. Father Valignano’s arrival and presence in Kyoto reaffirmed this. Whilst in central Japan, the great missionary also spent some time visiting all the churches in the region, baptizing many new Christians along the way, including a crowd of no less than 2000 in Takatsuki (高槻).

Soon after finishing his first visitation to Japan, Father Valignano decided to return to Rome to report all that he had seen and done to the Pope and the Jesuit Superiors. With the sponsorship of the three Christian daimyos of Kyushu, namely Otomo Sorin, Omura Sumitada and Arima Harunobu, Father Valignano brought along with him the Tensho Embassy, which comprised four young Japanese nobles under the age of 16. They thus departed from Nagasaki in February 1582. I will be covering more on the Tensho Embassy in a subsequent part of this article.

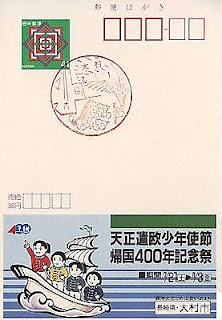

A postage card featuring the Tensho Embassy (天正使節, Tenshō Shisetsu), published by the Nagasaki Prefectural Government in 1990 to commemorate the 400th year anniversary of its return to Japan

Second Visitation to Japan (1590 – 1592)

Father Valignano accompanied the Tensho Embassy back to Japan as they set out from Goa in April 1588 and reached Macao in July 1589. Receiving news that Oda Nobunaga had committed harakiri in 1582 and that the formidable daimyo Toyotomi Hideyoshi (豊臣秀吉) (1536 – 1598) had succeeded the former’s place, Father Valignano was appointed as the Ambassador of the (Portuguese) Viceroy of India to Hideyoshi’s court in order to begin goodwill relations with the daimyo.

Nevertheless, upon landing in Macao, Father Valignano learned of the shocking news that Hideyoshi had issued an edict in 1587 banning Christianity throughout Japan and expelling all missionaries from the land. Also, Hideyoshi’s army had conquered the entire island of Kyushu, including the port-city of Nagasaki, and had placed the port-city under his direct control. (I will be covering more about these in the final part of this article.)

Toyotomi Hideyoshi (豊臣秀吉) (1536 – 1598), the second of the three greatest daimyos involved in the reunification of Japan

Unfazed by this news, Father Valignano travelled back to Nagasaki with the Tensho Embassy in July 1590. He learned that though the anti-Christian edict had been proclaimed, it was not implemented with complete strictness, as long as Hideyoshi’s anger was not aroused. As such, missionaries were still able to carry out their work clandestinely, but they had to be extremely careful so as not to do anything that may trigger Hideyoshi’s anger.

Shortly after his arrival in Nagasaki, Father Valignano made his way to Kyoto and arrived there in February 1591 to request an audience with Hideyoshi, but was resolutely refused. However, with the help of another Christian daimyo, Kuroda Yoshitaka (黒田孝高) (1546 – 1604), Father Valignano was granted an audience with the new ruler of Japan, but under the condition that the missionary speaks only in his capacity as the Ambassador of the Viceroy of India and makes no requests whatsoever for the edict to be repealed.

Christian daimyo Kuroda Yoshitaka (黒田孝高) (1546 – 1604)

During the audience, Father Valignano read out the letter written by the Viceroy of India in the presence of Hideyoshi and his subordinates. The letter, which was written before the declaration of the anti-Christian edict in 1587, expressed gratitude towards Hideyoshi for his goodwill towards the Jesuit missionaries in Japan and included a kind request from the Viceroy asking Hideyoshi to continue providing protection and support for them. Since Father Valignano himself was not permitted to make any explicit requests for the revocation of the edict, he hoped that the contents of the Viceroy’s letter might be able to deliver his message instead.

At the least, Father Valignano’s hope was realized to a certain extent. He was permitted to travel anywhere throughout Japan before Hideyoshi’s official reply to the Viceroy was completed. Hence, the great missionary grabbed this opportunity to visit all the Christian communities in central Japan. Also, Hideyoshi granted the permission for 10 Jesuit priests to remain in Nagasaki and gave indications that he would not take any further action against Christianity in Japan as long as there was nothing that occurred to provoke his wrath.

Reenactment of a scene from Toyotomi Hideyoshi's life - his cherry blossom viewing (花見, Hanami) parade held shortly before his death in 1598

Since Hideyoshi still refused to repeal the edict, Father Valignano left instructions for all remaining missionaries in Japan to be extremely careful in their work and not do anything that might anger the powerful ruler. Father Valignano also disallowed more missionaries from coming to Japan in order to avoid attracting more attention towards the presence of foreign Jesuits in the nation. Having done all these, he thus left Nagasaki for Macao in October 1592.

Third Visitation to Japan (1598 – 1603)

Father Valignano’s third and final visitation to Japan began when he landed in the port-city of Nagasaki in August 1598. This time, he received even more upsetting news that nearly broke his heart regarding the status of Christianity in Japan. Apparently, due to another unexpected incident that provoked his wrath, Hideyoshi commanded a brutal execution of the Twenty-six Martyrs of Japan in Nagasaki in February 1597. (This will be covered in further detail in the final part of this article.) Furthermore, almost all Jesuit missionaries were exiled to Macao in March 1598, while all the seminaries that Father Valignano had worked so tirelessly to establish before this were forcefully shut down.

An illustration of the martyrdom of the Twenty-six Martyrs of Japan in Nagasaki in February 1597

Despite all these, there were still a handful of Jesuit missionaries who secretly remained in Nagasaki. Efforts to purge Japan of Christianity slowly died down when Hideyoshi became ill prior to his death in September 1598. As the anti-Christian sentiments whittled off gradually, more daimyos came forward to offer their assistance and support for the remaining missionaries and Christian communities. Christian daimyos, especially Konishi Yukinaga (小西行長) (1555 – 1600), consolidated their support and protection for the Jesuit missionaries and Japanese Christians within their domains after the death of Hideyoshi. Many missionaries also came to carry out activities in the domains of non-Christian daimyos, being invited by the daimyos themselves.

Things also seemed brighter when Tokugawa Ieyasu (徳川家康) (1543 – 1616) came into power and succeeded Hideyoshi as ruler of Japan after the Battle of Sekigahara (関ヶ原の戦い, Sekigahara no Tatakai) in 1600. I will not go into much detail about the Battle of Sekigahara, but as far as this article is concerned, it is essential to know that this major battle broke out due to numerous disputes as to who would succeed Hideyoshi’s place. Loyalists of Hideyoshi sided with his son, Toyotomi Hideyori (豊臣秀頼) (1593 – 1615), whom they saw as the legal heir to Hideyoshi’s place. However, there were also many daimyos who sided with Ieyasu and was supportive of his efforts in claiming Hideyoshi’s position as ruler of Japan. The outcome of the battle was that Ieyasu gained victory and claimed that position.

A reenactment of the Battle of Sekigahara (関ヶ原の戦い, Sekigahara no Tatakai)

In order to gain the favour of the new ruler, Father Valignano sent congratulatory letters to Ieyasu, where he also made subtle requests for Hideyoshi’s anti-Christian edict to be repealed. At that time, Ieyasu’s position as ruler had not been properly established yet, so he tried to avoid making new enemies by all means possible, including giving a favourable reply to Father Valignano. In his reply, Ieyasu stated that he could not immediately repeal Hideyoshi’s edict, but he gave his assurance that he would, by all means, do his best to grant full freedom of religion for the Christians – a statement that he later contradicted brutally.

With Ieyasu’s initial reassurance procured by Father Valignano, missionary activities could be resumed peacefully and the Japanese Christian communities and daimyos could breathe a sigh of relief. Nevertheless, Japanese Christianity lost its greatest protector and patron of the era when Ieyasu ordered the execution of Konishi Yukinaga in 1600. This was because Yukinaga had sided with Toyotomi Hideyori in the Battle of Sekigahara, as mentioned above. Kuroda Yoshitaka, a Christian daimyo whom I’ve mentioned above, took Yukinaga’s place as the next protector and patron of Japanese Christianity.

Tokugawa Ieyasu (徳川家康) (1543 – 1616), the last of the three greatest daimyos involved in the reunification of Japan

With the Battle of Sekigahara just concluded, the country now free of civil wars, Ieyasu’s positive reassurance towards Christianity and Yoshitaka’s continual protection, Christianity was able to flourish once again in the Land of the Rising Sun after 1600. Father Valignano was thus able to restore the seminaries that Hideyoshi had shut down and reestablish Nagasaki as the main hub of Christian activities in Japan. With many signs of positive growth of Christianity in Japan once again, Father Valignano subsequently left Japan in January 1603 with peace and joy in his heart. The great missionary died in Macao in January 1606, not knowing that one of the worst persecutions in the history of Christianity throughout the world was about to occur in the very same land where he had poured out much of his sweat and tears for the sake of the gospel.

(Continued in next part)

(Continued in next part)

Main References:

1) Cieslik, H. (1954) Early missionaries in Japan 5: Alessandro Valignano: Pioneer in adaptation, Jesuits of Japan, viewed 29 November, 2010, <http://pweb.sophia.ac.jp/britto/xavier/cieslik/ciejmj05.pdf>

It is too sad to realize no one has read your MOST IMPORTANT information and commented on it.

ReplyDeleteYou must realize this is one of the greatest secrets the devil keeps outside of the biggest one in history to me--the Chrianization of the Plains Indians in America by Father Pierre DeSmet. Our "Ghost Dance in the late 1890's was all of those baptized chiefs and their tribal followers dancing in the snow while begging Jesus Christ to come back and free them from the horrible white men. That history I know to well, so when I stumbled across the same event in Japan, EQUALLY buried and hidden from most eyes, I was literally awash, as they say, with sorrow and sadness.

There were almost 2,000 Christian communes or monk retreats, one history book reports. Can't find it again. You know where I found this hidden history? Researching Chinese and Japanese art! In an ART BOOK. Insane, but true.

Is the website available in Japanese? Of course I assume it is.

I would love more dialogue with you. Do you want to help me reveal the worst secret of American history on your website? I will never, never have the time to do it myself.

For instance did you have any idea on earth that the morning Sitting Bull, a convert from 1860's on, told the soldiers before they shot him, "I don't have time to talk to you. I'm going to Pine Ridge TO SEE GOD."

They were Ghost Dancing there and they believed Christ was about to appear and were apparently all waiting for Sitting Bull. I have to get the official gov. military records to find that and haven't had time.

sincerely,

Jane Hafker

jhafker@aol.com