Chess

as it was when it was first introduced into Europe about a millennium ago

differed in several aspects from the chess that we know today. Modifications

and variations effected upon the rules of gameplay and the forms that the chess

pieces took have distinguished modern chess from its ancient precursors in many

unique ways. Having covered these in the previous part of this article, let us

now proceed with the final part of this article, where I will be briefly

covering on the modern history of this ever-popular game.

While

the Church in the first half of the previous millennium often perceived chess

to be an illness and a vice in society, the Church in the second half viewed it

in a different light altogether. Indeed, chess had swelled so much in popularity

that from the 1500s onwards, Protestant movements around Europe that strongly

criticized many pastimes as “ungodly pursuits” often stood in defence of chess.

This further propelled the popularity and general acceptance of chess as a

“legitimate” pastime, consequently making it an integral part of European

society.

In

the latter half of the previous millennium, literature on the theories and

strategies of chess grew, as more and more books were written on the subject by

skilled mathematicians and seasoned players who dedicated much of their time

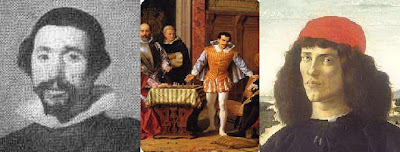

studying the game. Early chess masters such as Luis Ramirez de Lucena (1465 –

1530), Giovanni Leonardo de Bona (1542 – 1587) and Ruy Lopez de Segura (1530 –

1580) contributed much to studying and analysing different elements of chess

openings and endgames.

Chess masters of the Renaissance era. From left: Luiz Ramirez de Lucena (1465 - 1530), Giovanni Leonardo de Bona (1542 - 1587) and Ruy Lopez de Segura (1530 - 1580)

Come

the 18th and 19th centuries, the centre of European chess

life shifted from southern Europe (Spain and Italy) to northern European

countries such as France and England. Luxurious coffee shops such as the Café de la Régence in Paris and

Simpson’s Divan in London became prominent centres of chess life, where many

professional chess players would gather to challenge each other and exchange

knowledge. It was during this era that chess masters such as François-André Danican Philidor (1726 – 1795), Louis-Charles Mahé de La Bourdonnais (1795 – 1840) and Alexander

McDonnell (1798 – 1835) carved their names in the world of chess.

Café de la Régence in Paris, one of the most renowned centres of European chess life in the 18th and 19th centuries

One

of the most celebrated chess events of this era was a renowned series of six matches

between La Bourdonnais and McDonnell in the summer of 1834 in the Westminster

Chess Club in London, of which the outcome was victory for the former. Until

today, this series of six matches has been widely regarded as one of the

earliest unofficial World Chess Championship tournaments, with La Bourdonnais

being regarded as the unofficial World Chess Champion at that time when such a

title was not yet in existence.

Louis-Charles Mahé de La Bourdonnais (1795 - 1840)

With

the progress of the 19th century, chess rapidly grew to become an

organized sport. Chess clubs mushroomed throughout Europe, and numerous chess

books and journals were published by and for chess enthusiasts. Friendly and

competitive matches between chess clubs became a norm, whereby chess

professionals would gather together, play matches against each other and

exchange ideas on chess theories. Nonetheless, with the growth of chess as a

modern sport and pastime, the game was still regarded as being exclusively a

gentleman’s game; a game played by elite, aristocratic and educated men. Such

an image of chess remained until the early 20th century.

The

modern development and organization of chess also meant that its rules of

gameplay became more well-defined and standardized throughout the world. This

standardization of rules thus made it possible for large-scale chess

tournaments to be organized at the international level. The 1851 London Chess Tournament,

proposed and organized by English chess master Howard Staunton (1810 – 1874),

was the first such tournament ever to be held in such a large scale, having

been participated by chess masters from the UK, Germany, France and Hungary,

including Staunton himself. The tournament saw Adolf Anderssen (1818 – 1879) of

Germany emerge victorious, subsequently being crowned the unofficial World

Chess Champion of that time.

The Immortal Game, one of the most celebrated chess games of all time, played by Adolf Anderssen and Lionel Kieseritzky during a break in the 1851 London Chess Tournament. It is described as a game that is "perhaps unparalleled in chess literature"

As

international tournaments, both formal and informal, became a growing trend in

the rapidly transforming world of chess, many chess players started to realize

that the game was lacking a vital element – a standardized set of chess pieces.

The problem arose due to the fact that chess pieces differed in appearance

according to region. Chess pieces used by the English may not look the same as

those used by the French, while the Germans used yet another set of chess

pieces which looked different altogether. The absence of a standardized design

for each chess piece proved to be a major disadvantage between international

players, particularly if one player was unfamiliar with the chess pieces that

his opponent was using.

The

earliest solution, which in fact later became the most widely accepted

solution, was proposed by Nathaniel Cook a few years prior to the 1851 London Chess

Tournament. With the help of his brother-in-law, John Jacques, Cook produced a

unique design for each chess piece that combined elements of neoclassical and

Victorian influence. Patented in 1849 and mass-produced thereafter by John

Jacques of London (an established company headed by John Jacques himself that

manufactured and supplied sports and game equipment), the new set of chess

pieces soon after became a hit within the English and European chess community.

This was not without the help of Howard Staunton himself, who publicly approved

and even promoted the new chess set on behalf of the company. The chess set was

consequently called the Staunton chess set, which then became the official set

endorsed by the World Chess Federation in 1924 for future use in all

international chess tournaments.

Original Staunton chess set

In

the wake of the 1851 London Chess Tournament, one major problem came to

attention: the amount of time players took to make a move. Participants of the

tournament frequently took hours to think before deciding on a move, and this

became a huge setback to the smooth organization of the entire tournament. In

subsequent years, time limits were suggested and employed in official

tournaments. Several variants of such time rules existed, in which some

tournaments allowed each player five minutes to decide on a move while others

allowed a certain period of time for a fixed number of moves to be made e.g. 2

hours for 30 moves. Players who failed to conform to the time rules were either

fined or, more severely, forfeited from the game. In some tournaments, players

who made a particular number of moves within a predetermined time frame were

rewarded with additional time for subsequent moves. These time rules thus

became a new and integral part of every official chess tournaments thereafter.

In

an era when digital clocks were still non-existent, timekeeping in chess was

often accomplished using either sandglasses or pendulums. As technology

progressed at the turn of the 19th century, analogue clocks became

the accepted standard for timekeeping, and these were then replaced by digital

clocks since the 1980s. Presently, official chess tournaments employ two

parallel clocks per game, whereby a player is required to press a button to

activate the timer after completing a move.

Parallel clocks used in official chess tournaments

Talks

and suggestions about crowning the world’s strongest chess player as the World

Chess Champion had been rife since the 1851 London tournament, but it was not

until 1886 that the prestigious title became officially recognized. Since

Anderssen’s decisive victory in the 1851 London tournament, several

international tournaments equivalent to today’s World Chess Championships had

been played, which saw Anderssen’s unofficial title being transferred into the

hands of Paul Morphy (1837 – 1884), an American, in 1858. Nevertheless, because

Morphy made an early retirement from active chess before being defeated by any

worthy opponent, he was not the only one who was unofficially recognized as the

World Chess Champion at that time. Wilhelm Steinitz (1836 – 1900), an Austrian

by birth, who narrowly defeated Anderssen in a tournament in 1866, also reigned

as unofficial World Chess Champion alongside Morphy at that time. Indeed, this

match between Steinitz and Anderssen is now widely accepted by historians and

chess professionals as the first ever official World Chess Championship.

Match between Adolf Anderssen and Wilhelm Steinitz in 1866. This match is now widely accepted as the first ever official World Chess Championship

The

1886 World Chess Championship was undoubtedly the first ever official

tournament that was held with a predefined aim of declaring the World Chess

Champion. Played by Wilhelm Steinitz and Johannes Zukertort (1842 – 1888), a

Polish by birth, the championship saw the two prominent players battling it all

out for the prestigious title in a series of 20 matches in New York, St. Louis

and New Orleans, in which the first player to achieve 10 wins was considered the

winner. The outcome of the competitive tournament was a decisive win for

Steinitz, who won 10-5 and thus became the first person to be officially

declared the World Chess Champion.

Wilhelm Steinitz (left) playing against Johannes Zukertort (right) in the 1886 World Chess Championship, resulting in Steinitz being declared the first official World Chess Champion

In

spite of this, the 1886 World Chess Champion was, in actual fact, not organized

by any official body governing the game. It was more of an informal series of

matches that garnered much media attention and scrutiny across the world of

chess. Until 1946, if one wished to become the World Chess Champion, one had to

challenge the existing champion and self-organize the match. Financing for

travel and venue had to be borne by the challenger himself, and if he defeated

the incumbent, he would be declared the new champion.

In

order to ensure a smoother and more organized process of holding championship

tournaments and governing chess rules, attempts were made at several

international tournaments, namely the 1914 St. Petersburg, 1914 Mannheim and

1920 Gothenburg tournaments, to establish an international chess federation.

Nonetheless, World War I and its aftermath hampered such attempts. Finally,

during an international chess tournament held in Paris alongside the 1924

Summer Olympics, a successful attempt was made to establish the Fédération Internationale des Échecs

(FIDE), or World Chess Federation, which was rather powerless and poorly

financed in its first few months after initiation.

International chess tournament held alongside the 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris

With

FIDE’s gradual growth and expansion, it soon gained more influence in the

worldwide chess arena. In its 1925 and 1926 congresses, it expressed its desire

to become the official body responsible for managing future world championships,

and it worked hard towards achieving that goal. In 1927, FIDE successfully

organized its first official Chess Olympiad in London, which saw the

participation of 16 international teams. However, because it did not involve

any match for the World Champion title against the incumbent champion, the

Chess Olympiad could not be considered a World Chess Championship.

In

attempting to gain recognition and acceptance as the official organizer of the

World Championship, FIDE proposed a system in which potential challengers for

the championship will be screened and selected by a committee. This proposal

did not go down well with the international chess community. Instead, another

selection system proposed by the Dutch Chess Federation was more favoured,

whereby ex-champions and rising star players were to be gathered in a

preliminary tournament to select the next challenger for the championship. In

line with its proposal, the Dutch Chess Federation then went on to organize the

AVRO Tournament in 1938 which, despite not being officially endorsed as a

selection tournament, managed to attract the best chess masters in the world at

that time, including incumbent World Champion Alexander Alekhine (1892 – 1946)

and former champions José Raúl Capablanca (1888 – 1942) and Max Euwe (1901 –

1981). This stirred much controversy amongst the worldwide chess community, but

things were soon cut short with the outburst of the Second World War in 1939.

Alexander Alekhine playing against Reuben Fine in the 1938 AVRO Tournament

As

the Second World War rampaged much of the world, international chess

competitions saw an absolute standstill and FIDE went into a nearly decade-long

hiatus. By the time the war ended in 1945, much of the world was in a deep

economic slump following excessive spending on defence and military affairs.

Although FIDE once again became active in 1946, it was faced with severe

financial deficits and the inability on the part of many countries to send

representatives for tournaments due to lack of funding. Nonetheless, the

biggest dilemma that FIDE was confronted with was the death of Alexander

Alekhine, the reigning World Champion at that time. This literally meant that

Alekhine “died and brought his title with him to the grave,” as no one was able

to defeat him and thus succeed the much coveted title.

Many

solutions were proposed, but FIDE ultimately chose to bring together all the

surviving participants (or substitutes proposed by their respective

governments) of the 1938 AVRO Tournament in another major tournament to

determine the new World Champion. This resulted in the 1948 World Chess

Championship, held partly in The Hague and partly in Moscow, which marked the

beginning of FIDE’s official right to organize and coordinate all future World

Championship tournaments. Participated by five chess masters of that time,

Mikhail Botvinnik (1911 – 1995) of the then Soviet Union emerged victorious and

was crowned the new World Champion.

The five chess masters who participated in the 1948 World Chess Championship. From left: Max Euwe, Vasily Smyslov, Paul Keres, Mikhail Botvinnik and Samuel Reshevsky

Since

then, the World Chess Championships under FIDE have undergone much modification

and have even been embroiled in controversies from time to time. This included

a period of breakaway from FIDE under the leadership of former World Champion

Garry Kasparov (1963 – ), who went on to form the Professional Chess

Association (PCA) in 1993 as a rival organization to FIDE, even organizing its

own World Championships that resulted in more than one World Champion for several

years after PCA’s inception. (I will not go into detail about these

controversies.) Nevertheless, the World Championship tournaments reunified

under FIDE once again in 2006, and is now officially recognized as the ultimate

international chess tournament through which a chess master can seek to

challenge the reigning World Champion for the prestigious title. FIDE is now

recognized by the international community as the ultimate organization

governing the game of chess, boasting a membership of more than 150 countries

worldwide.

Former World Chess Champion Garry Kasparov

Indeed,

from its vague beginnings in the obscurities of a yet unknown India at that

time, chess has spread its wings to become one of the most widely acclaimed games

of today’s modern world. Not only does chess enjoy much popularity as both a

pastime and a competitive sport worldwide, it has also served as a brain

squeezer for many skilled mathematicians and chess masters who sought to find

solutions to the various statistical problems posed by the game or chessboard

itself. Doubtless to say, the popularity of chess has never waned since the

days of chaturanga, and it is here to

stay perhaps for as long as mankind still breathes.

Fédération

Internationale des Échecs (FIDE) or World Chess Federation, the international governing body for chess, currently headquartered in Athens, Greece

No comments:

Post a Comment