At the turn of

the 19th century, the far-sighted missionary vision of one man

brought Protestant Christianity into an ancient and elaborate civilization that

was still openly hostile to the message of the gospel. Taking a leap of faith

at the crossroads of missions, Robert Morrison did what no one at that time had

ever done – pioneering a Chinese translation of the whole Bible for mass

distribution, establishing mission centres in two metropolitan ports despite

the constant threats of persecution, and starting a missionary college that

soon extended its works to several parts of Southeast Asia. Indeed, the

remarkable life of this exemplary missionary, which I have illustrated in the

previous part of this article, is perhaps unmatched to any of his

contemporaries in China and Southeast Asia.

Nonetheless,

when one talks about the history of Christianity in the Middle Kingdom,

particularly Protestant Christianity, there is but one name that will always

stand out, etched in the historical annals of Christian missions and

immortalized sermon after sermon in Protestant churches throughout the globe.

Indeed, his name has become so synonymous with the spirit of Christian missions

that it would be a grievous offence not to mention it in any discourse

regarding the history of Christian missions, especially in China. That name is

none other than James Hudson Taylor (戴德生, Dàidéshēng)

(1832 – 1905).

James Hudson Taylor (戴德生, Dàidéshēng) (1832 – 1905)

“No other missionary in the nineteen centuries since the Apostle Paul has

had a wider vision and has carried out a more systematised plan of evangelizing

a broad geographical area than Hudson Taylor.”

Such was the summary of Taylor’s

life, as written by historian Ruth Tucker. His vision of bringing the gospel to

China was enormous and unparalleled, although he started off his maiden voyage

to the Middle Kingdom with nothing much but his humility in prayer and some

supplies at hand. Nonetheless, it was this humility in prayer that supplied him

everything that he required for his subsequent perilous missionary travels

throughout the great empire. If there was a single Bible verse that could

summarize Taylor’s entire philosophy in life, it was this:

“And whatever you ask in My name, that I will do, that the Father may be

glorified in the Son.” – The Gospel

According to John 14:13

“你们奉我的名无论求什么,我必成就,叫父因儿子得荣耀。” – 约翰福音14:13

Taylor’s life and philosophy of “in faith believing, in prayer receiving” was the very foundation

of all his missionary activities and his existence. It was his lifelong custom

that whenever he was in need of anything, he would first and foremost present

his requests and needs before God in prayer, and God would then prove his

faithfulness by miraculously supplying his every need without fail, as

evidenced from his personal writings and testimonies. Even before his arrival

in Shanghai (上海, Shànghăi)

in 1854, his life and conversion in England was filled with miraculous signs,

and his study of the Chinese language and medicine showed exceptionally speedy

progress. If I were to cover the details of his life before his first arrival

in China in 1854, this will indeed be a very long article, and since this

article is mainly intended to give you an overview of Christian history in

China during the late Qing Dynasty, I will mainly be focusing on Taylor’s life

and missionary activities in China. Nevertheless, if you are interested to read

more about his personal life and conversion before beginning his mission in

China, feel free to read it from this website.

Hudson Taylor in his younger days

After a tumultuous and nearly disastrous voyage that

lasted for about 5 months, Taylor reached China for the first time in March

1854, landing in Shanghai only to find that the land was embroiled in a

large-scale civil war known as the Taiping Rebellion (太平叛乱, Tàipíng Pànluàn). (The Taiping Rebellion

was a civil war that sought to establish a pseudo-Christian Chinese state known

as the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom (太平天国, Tàipíng

Tiānguó).) His initial attempts at settling down in Shanghai were not very

successful due to the civil war, but he persevered and was finally able to

establish a small mission by the following year. He frequently went on short

trips around Shanghai by foot or by boat, proclaiming the gospel, distributing

Christian materials and providing simple medical services to the sick.

Hudson Taylor traveled by boat around the canals and waterways of Shanghai to preach the gospel

Taylor was very gifted in his missionary endeavours.

Whenever he went out on mission trips to proclaim the gospel in public spaces

around Shanghai, he would unfailingly draw large crowds of people to him, all

eager to hear his message. However, during his first few trips around Shanghai,

little did he realize that it was not his message or his oratory skills, but

rather his Western-styled appearance and attire that got him so much attention

from the crowds. In those days, the sight of an Englishman with sand-coloured

hair and a black English overcoat was a sight to behold for the Chinese, and

many of those who came to listen to him were often more interested in his

intriguing attire than the content of his message.

He soon realized that his completely foreign

appearance, despite his fluency in the Chinese language and local dialects,

became more of a subject of scrutiny and curiosity than his message of the gospel.

He discovered that although he spoke and understood the Chinese language and its

local dialects, his overtly Western appearance made him stand out all the more

as a foreigner and a stranger. Pondering over the matter for some time, he then

came to the conclusion that he should take on a traditional Chinese appearance:

shaving his head, keeping a pigtail at the back which he dyed black and wearing

a satin Chinese robe and shoes. And he acted on his decision without delay.

Taylor in traditional Chinese clothing

His new Chinese-style appearance had profound and

far-reaching effects on both his audience (the local Chinese) and his fellow

countrymen (the Englishmen) who settled in Shanghai. To the Chinese, Taylor

became an honoured guest and a revered teacher, and his missionary excursions

soon drew large crowds that were more interested in what he had to say than

what he was dressed in. To his fellow Englishmen in Shanghai, however, Taylor

was shunned as a lunatic and a lowlife, attempting to destroy the prestigious

image of the aristocratic Englishmen in the eyes of the Chinese. This did not

waver him, and he persevered with his newfound idea of adopting Chinese attire

and lifestyle – a move that virtually no other missionary from his era would

have even thought about.

Taylor adopted a unique way of bringing the gospel

to the Chinese communities he encountered. While many Protestant missionaries

before and during his era adopted ways which sought to draw people to the gospel rather than bring it to them, Taylor did the exact opposite. In the various

towns and cities that he went to (which I will be mentioning subsequently), he

based all his missionary efforts on a single principle, that is to bring the

gospel to the Chinese by going

directly to them, both physically and also culturally. In all his missionary

dealings, he was particularly sensitive to Chinese culture and customs,

respecting them and even adapting them into his lifestyle wherever possible.

Despite that, he lived an exemplary Christian life of prayer and devotion,

leading an example for new believers on how they could live devout Christian

lives in a Chinese context. To everyone whom he encountered, especially critics

from his fellow countrymen, Taylor emphasized the fact that he was in China to bring Christianity and not Western

culture to the Chinese.

Taylor faced many difficulties during his maiden sojourn in Shanghai, as illustrated in this caricature, where a thief attempts to rob him while he was asleep on the stone steps of a temple

After some time in Shanghai, Taylor relocated to

Ningbo (宁波, Níngbō),

one of the five Chinese treaty ports that was opened by the Treaty of Nanjing

in 1842. While in Ningbo, he met his wife, Maria Jane Dyer (1837 – 1870), who

was then working in a girls’ school opened by one of the first few female

missionaries in China, Mary Ann Aldersey (1797 – 1868). Taylor took up the

responsibility of managing a hospital in Ningbo which was previously run by Dr.

William Parker, a medical missionary to China. Although faith and prayer were

Taylor’s vital driving factors in managing both the hospital and his missionary

activities, the stresses that came from these soon started taking a toll on his

health, thus he subsequently decided that a temporary trip back to England in

1860 would give him a much needed brief respite.

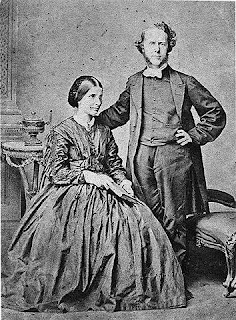

Hudson Taylor and his wife, Maria, in 1865

The six years that Taylor spent back in England were

indeed productive in preparing for his subsequent missionary trips to China. He

wasted no time at all; he made tremendous efforts to speak in the various

churches throughout the British Isles to promote the spiritual needs of China

and to share his experiences. He also wrote a book entitled China’s Spiritual Needs and Claims,

which served to attract much attention for missionary efforts to the Chinese. Taylor’s

efforts were not in vain; many church leaders and Christians who heard his

message came forward to pledge funds, and some even offered to follow him to

China on missionary trips.

Taylor’s

untiring efforts in promoting missionary needs in China culminated with the

founding of a new missionary society on 25 June 1865 in Brighton. That day, he

sat by the beach, praying fervently for hours long for a single request: that

24 willing, skilful missionaries, two for each of the 11 inner Chinese

provinces and two for Tibet (西藏, Xīzàng) and

Xinjiang (新疆,

Xīnjiāng), be sent to China to

further enhance missionary activities throughout the land. Indeed, that prayer

marked the birth of the China Inland Mission (CIM), or what is known today as

the Overseas Missionary Fellowship International (OMF International), and in less

than a year, the newfound society managed to raise over £2000 (approximately

£130,000 in 2007 terms) from the generous gifts and pledges of many Christians

and churches throughout the British Isles.

Overseas Missionary Fellowship International (OMF International), an international and interdenominational missionary organization today that has its roots in the China Inland Mission (CIM)

The founding of the CIM was a major turning point

that redefined the history and fundamental values of Christian missions

worldwide. Through the CIM, Taylor became one of the earliest pioneers and

advocators of the concept of “faith missions,” which essentially implies that

missionaries working under this concept should trust fully in God for the

provision of all necessary resources. It was this concept that became the core

philosophy and driving principle of the CIM, setting it apart from all its

other contemporaries. In line with this concept, the CIM permitted no

deliberate solicitations or collections of funds amongst its members, instead

requiring them to lay any need before God in prayer, faithfully believing that

God will supply adequately all their needs at the appropriate times. And as

they say, the rest is history. Funds and monetary gifts came pouring in without

fail every time its members prayed for their needs, as can be testified from

the various records of CIM/OMF’s history of missions.

It wasn’t only the concept of faith missions that

set CIM apart from many other missionary societies of that era. Unlike its

contemporaries, CIM accepted candidates for its missionary activities not based

on one’s denomination, gender, background or theological qualification, but

based on one’s personal faith in all fundamental truths of the gospel. In other

words, the CIM accepted men and women from all Christian denominations, and

even ordinary laymen who were not highly educated or who had never undergone

formal theological training could be accepted for the missionary field, as was

the case for most of its members including Taylor himself. Most importantly, a

strong personal faith in the basic principles of the gospel and a willingness

to commit oneself to the missionary field were the prerequisites that Taylor

sought for in all his recruits.

Taylor and some of his missionary candidates in 1865

CIM was very distinct in the way it carried out its

missionary activities. All its missionaries, both men and women, were required

to don traditional Chinese clothing while undertaking missionary activities,

which was a move that was much frowned upon by many other missionaries and

Englishmen in China who perceived Chinese clothing to be ungentlemanly and for

women, semi-scandalous. CIM missionaries were also required to live according

to the Chinese lifestyle as much as possible. Taylor adamantly defended these

decisions, asserting that the gospel would only be able to take root on Chinese

soil if Christian missionaries were sensitive to Chinese culture and were

willing to affirm their lifestyle and customs as much as was permissible by the

gospel.

A photo of CIM missionaries in traditional Chinese clothing, taken in April 1891. Taylor is seated in the second row, fifth from right

After

making all the necessary preparations, Taylor finally left England on 26 May

1866 with a large, new mission team under the CIM famously known as the

Lammermuir Party. A four-month journey with two typhoons en route was what it

took before they finally arrived safely in Shanghai on 30 September 1866.

The Lammermuir Party, CIM's first ever mission team

No comments:

Post a Comment